Estimated reading time: 17 minutes

Remembering information over an extended period of time is fundamental to learning. In a recent COBIS webinar, our Director of International Charles Wood explored what happens in the brain when we learn something new and how we can make remembering easier for students.

He was joined by Ben Cooper of GEMS Wellington Academy - Al Khail and Steffen Sommer and Christopher Watson of Doha College, who shared how they use this knowledge to enhance the teaching and learning at their international schools.

Understanding how memory works

When we first encounter a new piece of information, new connections between neurons – the specialised cells that make up the brain – are made. This pathway of different neurons is how that new information is encoded into our brains so that we can later retrieve it; it is not the end of the pathway, but the pathway itself that holds the memory. To remember that piece of learned information later on, the brain has to send a signal down that same pathway.

Given that that is the case, why can't we easily retrieve every single piece of information that we’ve ever learned? Why are some things far easier for us to remember than others? To understand this, we need to take a closer look at how memory works.

Every neuron in our brain makes roughly one thousand connections to other neurons, resulting in trillions of connections in total. The junctions where one neuron joins another are called synapses. When people talk about a ‘strong memory’ or a ‘weak memory’, what they’re referring to is the strength of every one of the synapses along that pathway, which is known as ‘synaptic strength’. We can improve the reliability and accessibility of a memory by increasing the synaptic strength.

The changes that occur in the synapses as they strengthen is called Long Term Potentiation, which increases the efficiency of a signal being transmitted from one neuron to the next. The faster and more efficiently this happens, the better we can recall a memory.

Fortunately, there are things we can do to strengthen our synapses. If I were to ask you to read a random 11-digit string right now, you probably wouldn’t be able to repeat it correctly just a minute or two after I stopped showing it to you, whereas if I asked you to tell me your phone number, you would be able to do so with ease. We remember things like our phone numbers because we use them frequently and consistently, and over time, that increases the Long Term Potentiation in the synapses of that pathway, making the memory stronger. We can apply the same logic to teaching and learning.

Active retrieval practice

Every teacher will have experienced teaching a great lesson on a new topic, during which the students appeared to be highly engaged and were able to answer every question correctly, only to return to the same class a few days later and find that the students have forgotten everything that was covered.

It is frustrating, but not surprising. What often happens is that as the students go from one problem to the next in a lesson, the information stays in their working memory. If they get distracted, they are able to simply look at their notes to remind themselves of what they need to do. The information is not prioritised by their long term memory, so when the students leave the lesson, the memory of what they have learned isn’t reliably stored.

However, as with the phone number example, we can help students to remember more of what they have been taught in the long term by providing them with frequent and consistent opportunities to retrieve that information. This is known as Active Retrieval Practice, and there are many ways of integrating it into teaching and learning.

The testing effect

One of the best ways to build active retrieval practice into your teaching is through the use of formative assessments, for example low-stakes quizzes and questioning. CENTURY can be used to quiz students, using the auto-marked question sets that are included in all of our mini-lessons, and we also have diagnostics that offer a closed book experience.

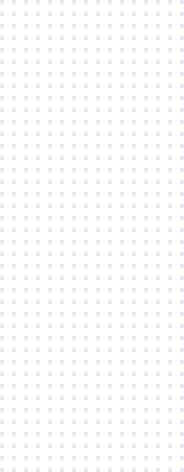

However you choose to carry out formative assessments, there is a significant amount of research that shows that it is much more effective to review information by testing yourself on it than passively revising.

The graph above contains the results of a study carried out by cognitive scientists Roedger and Karpicke. Students were asked to memorise prose passages, and those who followed the ‘study, test’ approach were able to remember a much higher percentage of the passages after one week than the ‘study, study’ students. The rate at which they were forgetting it was also far slower. There has been a substantial number of studies that have replicated this finding across different subjects and domains.

The forgetting curve

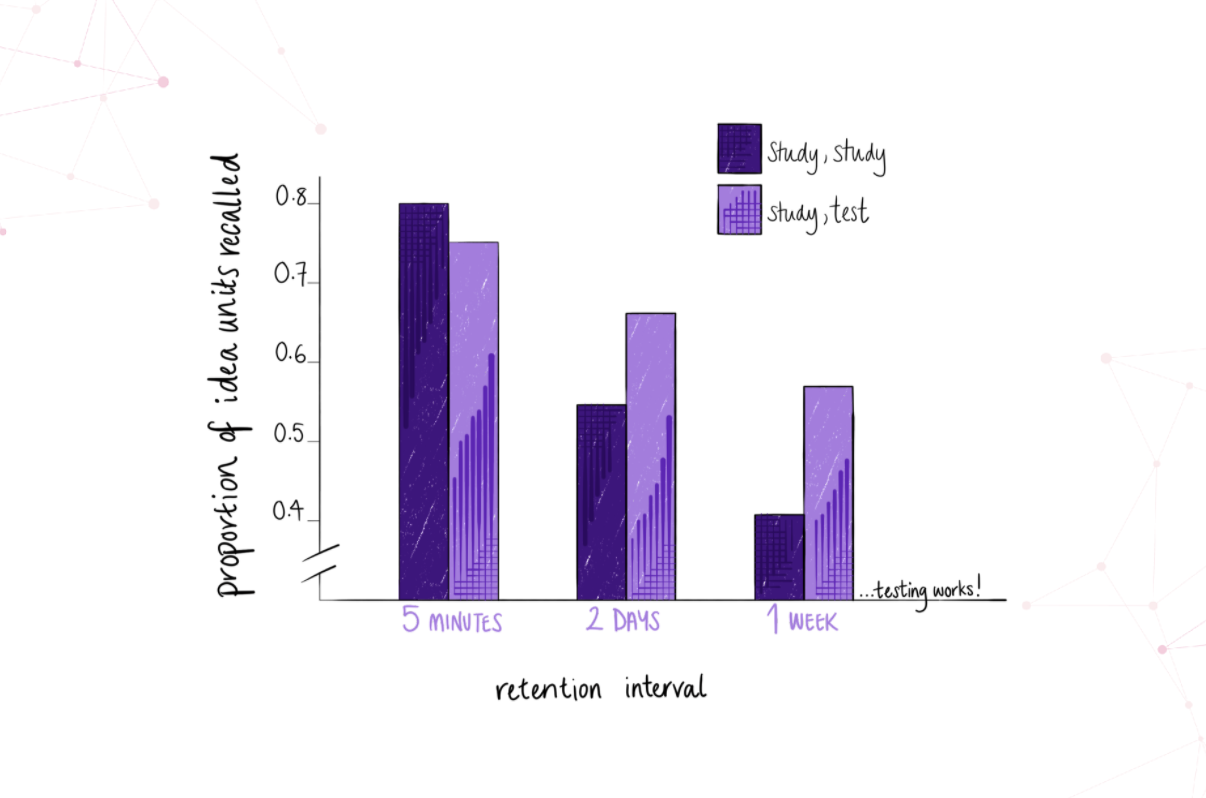

German psychologist Ebbinghaus made some important contributions to understanding how we learn, retrieve and forget information. He conducted hundreds and hundreds of experiments on himself to investigate the rate of forgetting over time and how reviewing the learning material impacted forgetting.

This graph above summarises his findings. In short, the first time you learn something, you’re going to forget it pretty quickly; however, if you revise that material at intervals – ideally when you can recall about 80% of what you learned – then you can increase the length of time it will take to be forgotten.

Spacing

Ebbinghaus’s findings have been echoed by further research, with cognitive scientist Karpicke’s research similarly concluding that memory degrades quickly if information is not reviewed. Despite this, students often ‘mass learn’ in schools, meaning that they study a topic in one go then move on to the next one, only reviewing the topic when they come to revising it for an exam.

Spaced learning is the principle that information is more easily learnt when it is split into short time frames and repeated multiple times, with time passing between repetitions.

For example, if you teach three 50 minute science lessons per week per class, you could break each of them into 3 equal chunks, using each chunk to teach a different subtopic. You would be covering the same amount of content in the same amount of time as though you had three separate science lessons in the week, but simply structuring the lessons in a different way.

A simple technique to build spacing into your teaching is to set homework a week ‘later’, meaning that each week the homework relates to what was taught the previous week. This is easy to do on CENTURY, as you can simply assign students the relevant micro-lessons and the questions will be auto-marked for you, but it can be achieved however you set homework.

Another way to incorporate spacing is to embed lots of small, low-stakes quizzes into your teaching, making sure that those quizzes contain information from previous topics.

Interleaving

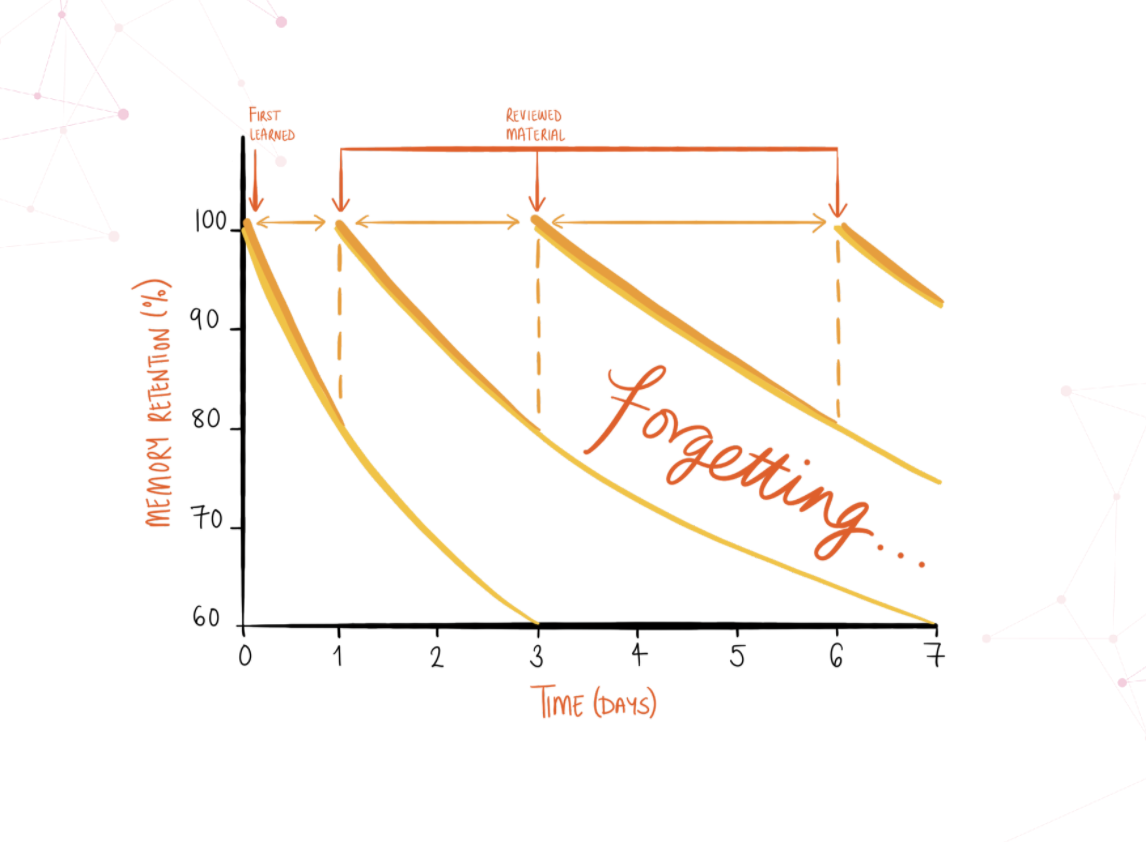

A similar theory that aims to minimise the forgetting curve is called interleaving, which is the mixing and alternating between ideas, concepts or skills when learning, as opposed to blocking, which is when students study one topic fully before moving on to another.

Traditionally a student studies everything in topic A, finishes and then moves on to topic B, and then to topic C. Interleaved practice is where topics are combined and used together. For example, a single skill such as ‘finding the slope of a graph’ is traditionally taught in a maths lesson, and once that has been taught, the class moves onto the next skill. Interleaved practice, on the other hand, would combine finding the slope of a graph with other mathematical skills during the lesson.

The graph above shows the results of a study that was carried out by Doug Rohrer, Robert F. Dedrick and Sandra Stershic with 7th graders learning algebra. There was a notable increase in scores immediately at the end of the 3 months of learning for students who had followed an interleaved programme, but even more impressive is how well those students had retained the information a month later. Those who learnt in the interleaved setting remembered nearly as well as they did just a day later, whereas those who learnt in the traditional blocked manner demonstrated a dramatic decrease in retention.

One way to implement interleaved practice into the classroom is to adopt a ‘station-rotation’ model, where students move in small groups between different activities. A CENTURY nugget is a good independent activity for students to complete, and the other activities can be designed to complement this.

The success of both spacing and interleaving is likely underpinned by providing more opportunities for active retrieval practice, promoting LTP changes in the brain. However, it is worth noting that there are some limitations to interleaving, most notably that some familiarity with a subject is initially required before interleaving will add benefit, and that it appears to be less impactful for students with EAL and SEN.

GEMS Wellington Academy - Al Khail

Ben Cooper, Primary Principal

As part of our neuroscience journey, we’ve been working on developing what we call the assessment loop, which we also refer to as Assessment as Learning. The act of retrieval practice is a really crucial part of the learning process, so we wanted to develop a cycle that would help us to implement it effectively and often.

Before we teach anything new, we do a quick diagnostic to figure out what the children can and can’t do and what preexisting knowledge they have to build upon. That is often automated, so that it’s not too onerous for the teachers to mark and so on, and using the data produced by those diagnostics, teachers can identify the children’s starting points and immediately start teaching at the right level.

Once the teaching has taken place, we incorporate retrieval practice by getting the children to return to a similar diagnostic to the one they initially took to figure out what they are able to retrieve and what they have forgotten so that we can revisit those areas.

The key aspect to this is deciding when that should happen. We don’t encourage teachers to do diagnostics right away, but rather to leave it some time after the unit of learning has taken place before asking the children to complete them. The fact that a child can score highly on a set of questions taken directly after they were taught a topic doesn’t necessarily give us very valuable information because, as The Forgetting Curve shows, they will most likely forget that information very quickly.

If a child is consistently completing diagnostic assessments accurately over a long period of time, we can then confidently say that it’s embedded in their long term memory. It’s once the learner is at that point that we encourage summative assessment, not beforehand.

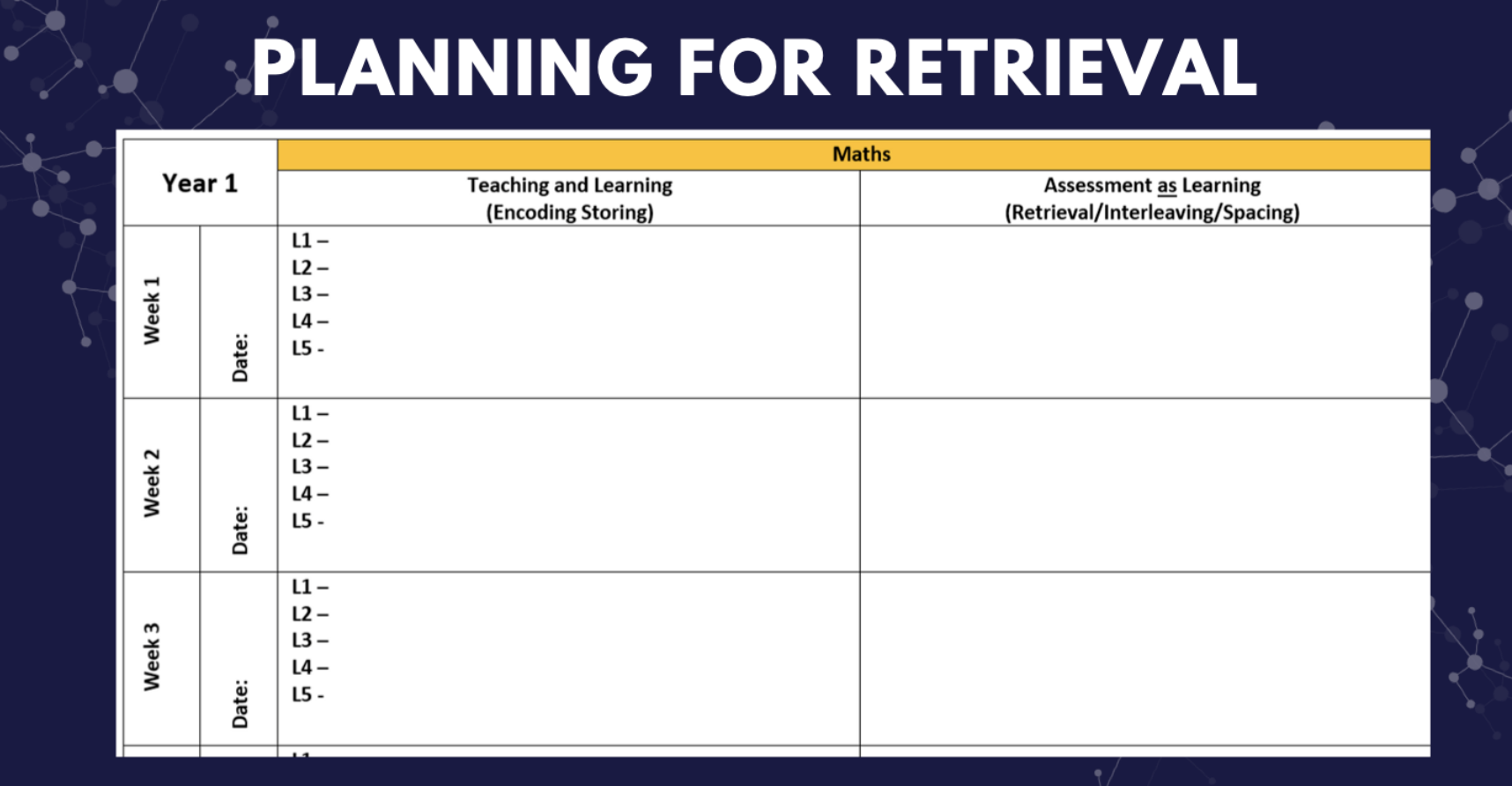

To ensure that we’re providing enough opportunities for retrieval practice and to help us decide what content needs to be prioritised for it, we’ve split our medium term plan into two. Before, what teachers focussed on was planning out what they were going to teach, for example the lesson objectives for the week, whereas now there’s an additional section that is used to plan out purposeful retrieval opportunities in the week.

We also have specific fluency targets for each year based on what learners need to know to move forward, for example things like multiplication fluency for Year 6 pupils, and we weave retrieval opportunities into that medium term plan to make sure that students are confident with them even if they haven’t been explicitly taught in a long time.

If it becomes apparent that the children are very confident with a topic, we can space it out a bit further, and if they aren’t, we can make the retrieval opportunities for that skill or topic more frequent.

Doha College

Steffen Sommer, Principal

Neuroscience is an integral part of everything we do at Doha College. As a HPL school, we believe that all children can be high performers, and that fundamental belief is supported by using CENTURY Tech and its AI.

I truly believe that this interleaving practice enhances the understanding of the material learned, which is absolutely crucial for the memorising process. Only if we’ve understood something are we able to remember longer term.

Christopher Watson, Deputy Head of Academic - Primary

As a High Performance Learning school, there are three things we’re really focusing on. One, the type of behaviours we want our learners to develop for them to be successful, two, the types of thinking skills we want them to have, and three, the learning process that is most efficacious to enable students to learn.

This ties in with Daniel T. Willingham’s quote ‘memory is the residue of thought’. By challenging children to recall knowledge and think harder and more deeply about what they have learned, we aim to strengthen their synapses and help them maintain more of what they learn in their long term memory.

We have built a number of retrieval opportunities into our teaching. For example, we have both an ‘Entry Ticket’ and an ‘Exit Ticket’, the former of which encourages active retrieval of knowledge by challenging children to think about their learning from the day before.

We also have a weekly review, when we interleave different topics from throughout the week so that the children are being challenged to think about different concepts in order to solve questions. We also include several questions on the same concept but of increasing difficulty within those reviews to help pupils develop mastery.

The image above is of what we call a retrieval clock, and it was created after about 3 or 4 weeks of learning a specific topic. The teacher used it to get pupils to think about all of the things they’d learned across that period of time, including prompts and scaffolds to help jog their memory.

To provide a comparison, if I asked a friend what they ate for dinner three weeks ago, they most likely wouldn’t remember. But if I said, “remember when we went to a restaurant a few weeks ago? What food did you order again?”, you’d find it far easier to remember. The idea with the retrieval clock is to activate different pieces of knowledge that make the overall learning experience much more memorable.

Book a demo to find out more about how CENTURY can help to enhance the teaching and learning at your school or college.