Estimated reading time: 12 minutes

Assessment, in its various guises, influences almost everything that goes on within a classroom. For the seven years I spent teaching mathematics, and during my time as Head of Maths, it defined my pedagogy. In short, effective, purposeful assessment tells us our students’ starting points, what they have mastered and what they need help on. It allows teachers to adapt to the needs of their students and to plan accordingly in order to ensure that every student is able to reach their full potential.

It’s important to pause here and consider the term ‘assessment’. As Dylan Wiliam, Emeritus professor of Educational Assessment at the UCL Institute of Education, explains, looking back on his and Paul Black’s seminal work, Inside the Black Box (2010), “I now think it might have been more productive to start with formative assessment as being responsive teaching.”

Discussing the work of psychologist David Ausubel, Wiliam goes on to say that “<...> any teaching should start from what the learner already knows, and that teachers should ascertain this, and teach accordingly.” It is also important to note, as Wiliam has done recently on Twitter, that ‘responsive teaching’ or ‘formative assessment’ isn’t one sided; the learner also has an important part to play.

Let’s dive into the various forms of assessment. This list is by no means exhaustive and definitions and names will, no doubt, be forever in flux. However, the following three are as good a starting point as any:

What is Assessment of Learning (AoL)?

Ask a layman to define ‘assessment’ and no doubt they will give you a definition of AoL. The key word here is ‘of’. Assessment of learning is summative and is usually conducted at the end of a unit of work: be that topic tests, end of year assessments and of course public examinations.

The purpose of AoL is to provide verifiable evidence of achievement to a variety of stakeholders: students, parents/guardians, employers and other educational institutions. Regardless of your thoughts on AoL and the objectivity placed upon these types of assessments, they play a huge part in our education system: they impact the design and implementation of schemes of learning, they leave an indelible impression on the structure of education delivery and are fundamental in benchmarking the educational performance of schools and entire countries (through PISA). When looking through the eyes of a learner, the impact of summative assessments could not be higher: employability, future earnings, self-worth and, according to a recent study, even life expectancy.

What is Assessment for Learning (AfL)?

In contrast to Assessment of Learning, assessment for learning happens during the learning process itself. It’s hard to put it better than Dylan Wiliam, who, during a keynote given at the University of Cambridge, describes AfL as “...the pedagogy of contingency.”

At its core AfL is about checking for understanding and being reactive as an educator. Learners are involved in the learning process, and by the collection and analysis of data, the teacher is able to adjust their teaching and delivery to maximise student understanding and progress.

Over the years teachers and educators have refined numerous strategies to check for understanding: Red/Amber/Green (RAG) ratings, low stakes assessments, starter quizzes, directed questioning, differentiation, exit tickets, seating plans and circulating the room, to name but a few.

Regardless of your preferred Assessment for Learning strategy, the key here is how you collect and act upon the data. To quote Wiliam, “<...> If you’re not using the evidence to do something that you couldn’t have done without the evidence, you’re not doing formative assessment.”

Assessment as Learning (AaL)

Perhaps this is an acronym you have yet to come across in education. Assessment as Learning builds upon the philosophy of Assessment for Learning, with a greater emphasis placed on feedback and metacognition. As Ruth Dann (2014) explains,

“It considers how pupils self-regulate their own learning, and in so doing make complex decisions about how they use feedback and engage with the learning priorities of the classroom.”

The idea here is to enable students to begin to learn about themselves as learners. In this sense students will begin to self regulate their own learning. The key to unlocking this metacognitive strategy is to equip learners with the tools to understand, interpret and act upon feedback.

Assessment as Learning creates reflective students who have the agency to decide on their next learning step.

As with any strategy that seeks to empower learners, AaL is often supported by the teacher at first. A successful approach to Assessment as Learning will have your learners asking the question, “What are the criteria for improving my work?” Strategies include, but are not limited to: regular peer and self assessment, regular and challenging practice, allowing students to question their own learning and creating an environment where taking chances and risking being wrong are promoted.

The importance of data to assessment

Herein lies a problem with a lot of formative learning strategies: the time involved in collecting data and being able to react to it. The Department for Education’s teacher workload survey from 2019 found that teachers are working on average a 50 hour week. I’m sure many teachers reading this now wished they were working only a 50 hour week...

So much of a teacher's time is spent collecting data that they will invariably have less time to interpret and react to said data.

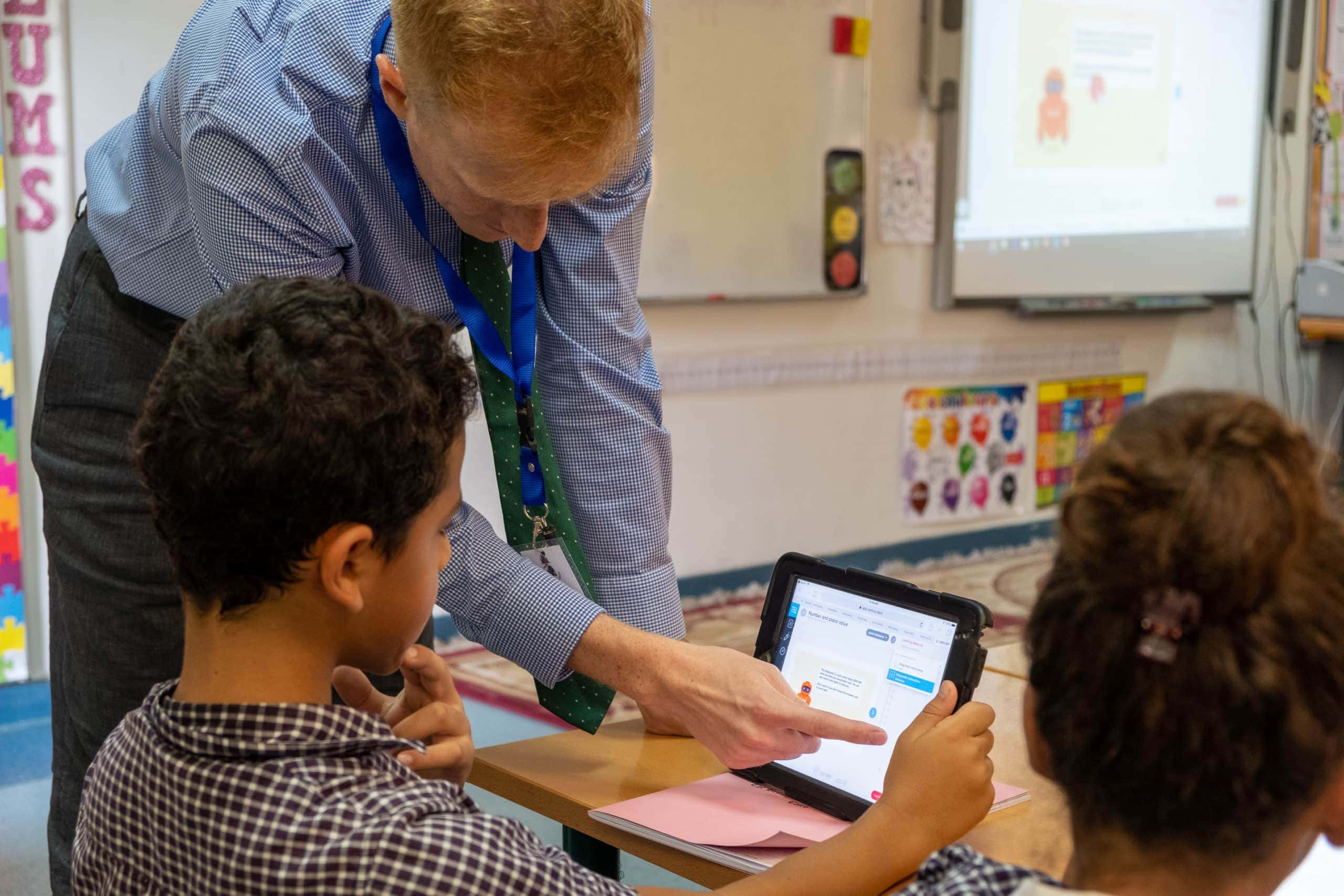

That’s one of the problems that the team of teachers, engineers and neuroscientists here at CENTURY are trying to solve. We have combined artificial intelligence with findings from neuroscience and learning science to create an adaptive, intelligent learning platform that improves the way children learn – but also equips teachers with detailed assessment data insights.

Using CENTURY for formative assessment

When students first log in to CENTURY they are faced with a series of diagnostic assessments. These assessments not only go on to provide students with a unique learner pathway, but they also provide invaluable data for teachers and leaders. The data from these baseline assessments is accessible as soon as a learner has completed one, there is no time delay in waiting for a teacher to have to mark and manually enter all of the data points.

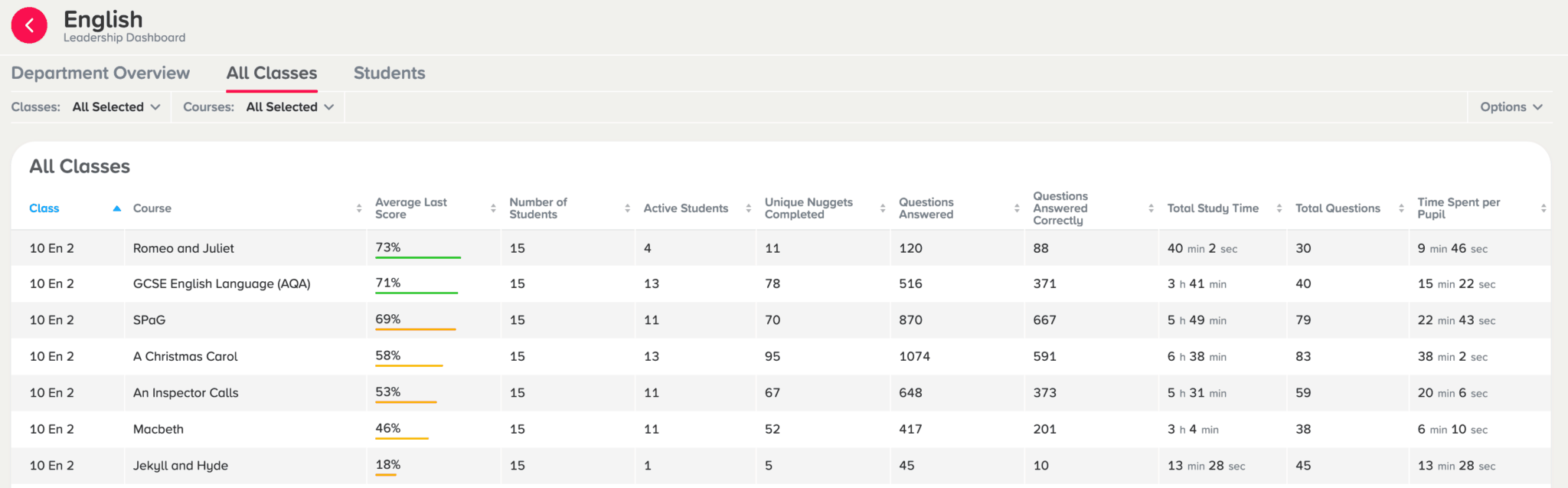

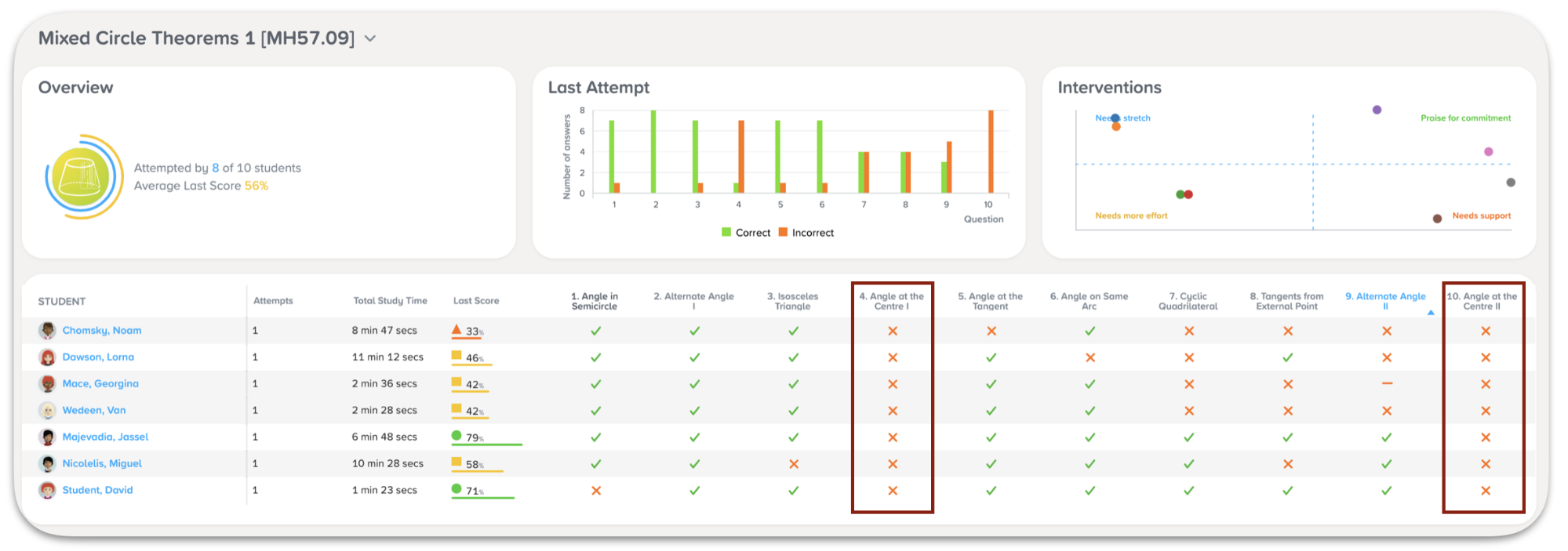

The above screenshot shows a class of students and immediately enables a teacher to pinpoint classwide weaknesses and misconceptions. During my time as Head of Maths, I created numerous versions of the above data page. I did it because it was incredibly useful, but it was also time consuming. Producing one of these for a class would require the creation of an assessment, marking the assessment and then manually entering each of the data points. This type of question level analysis (QLA) is generated in real time on the CENTURY platform and enables teachers to easily react to what they are seeing.

Remember, “AfL is the pedagogy of contingency” Wiliam (2016). In the above example I can quickly identify that my class needs support on inequalities. Digging deeper into the data I can see the exact type of question my learners have struggled with:

Being able to spend your time reacting to, and analysing, data frees you up to teach responsively to your students’ needs. These diagnostics work seamlessly as baseline assessments that can enable you to adapt or even create brand new schemes of learning.

The same QLA data page can be used to react to our students’ needs during the learning process itself:

Where diagnostic assessments enable teachers and leaders to adapt schemes of learning to meet their cohorts’ needs; the above data page enables classroom intervention. What stands out from the above is where my class has achieved a variety of results, they have all struggled with the exact same circle theorem. It is now clear what I should cover in our next lesson.

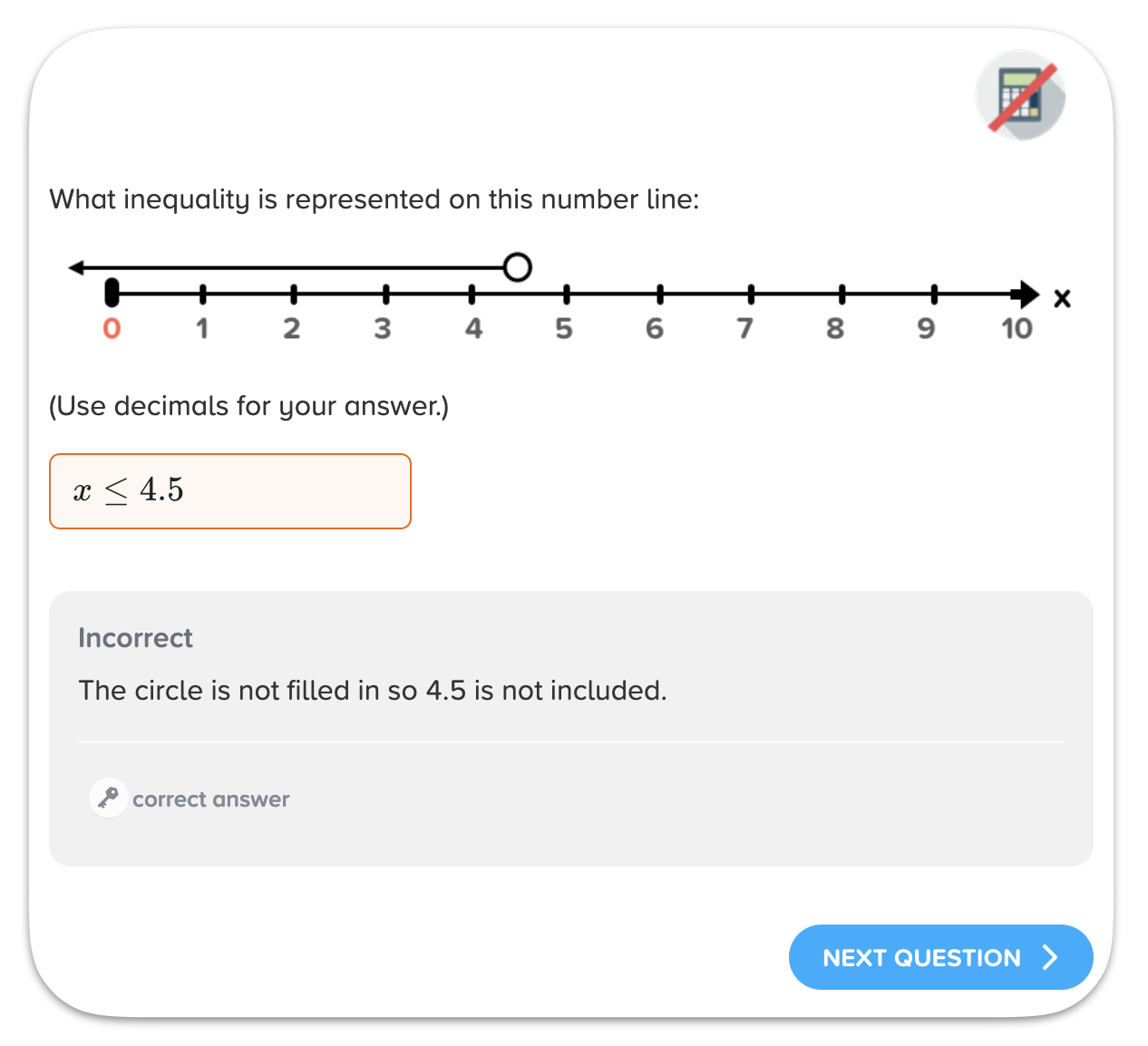

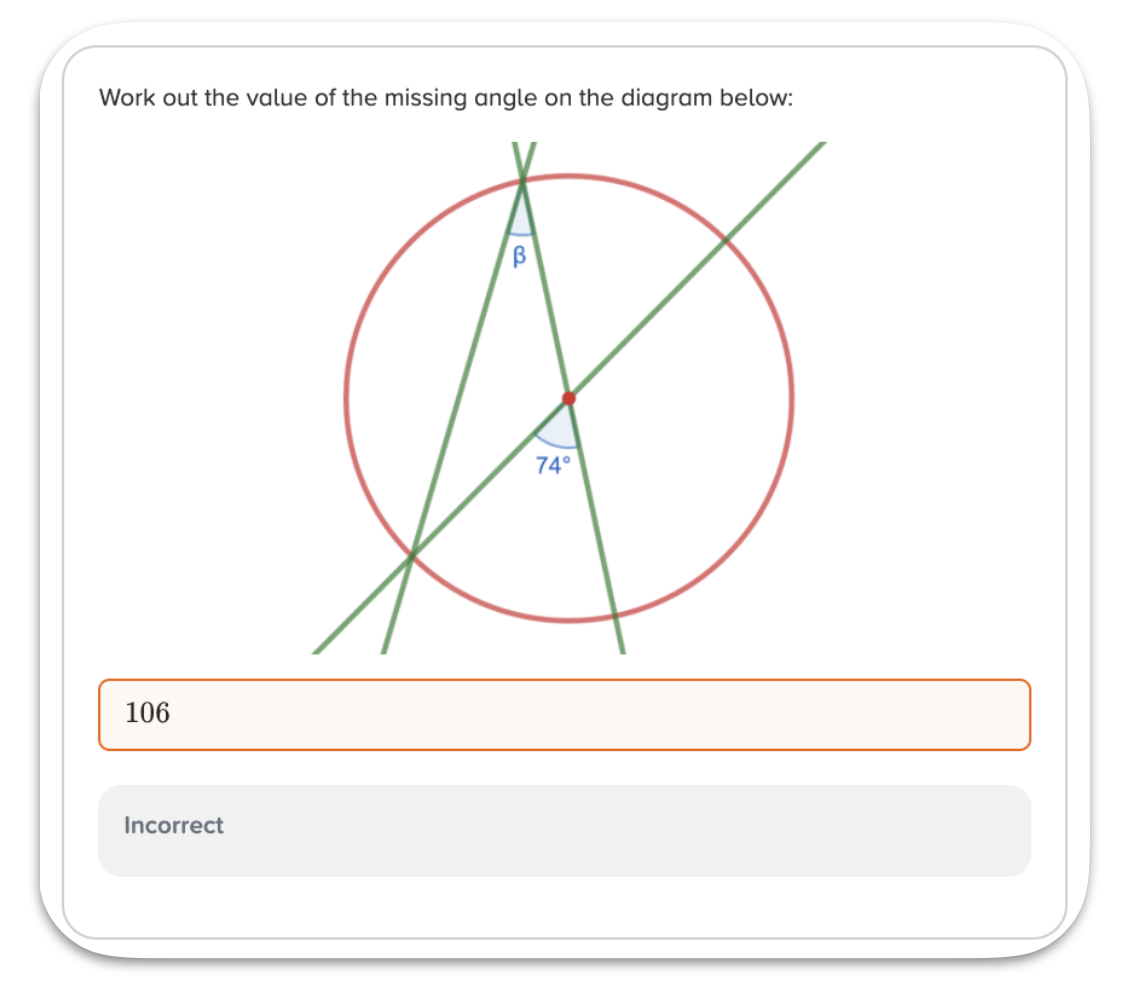

Again, digging deeper I can see the exact type of question my class struggled with, I can look at common misconceptions, and now have a clear end point for my next lesson.

Using CENTURY to increase learner metacognition

A key aspect of metacognition is to enable students to learn about themselves as learners.

The above data page is accessible to learners, teachers and also parents and guardians. It adapts in real time and provides essential information to enable students to begin to get a picture of their learning journey.

This student can identify their strengths and weaknesses and, using data insights, CENTURY is able to highlight areas of stretch and support.

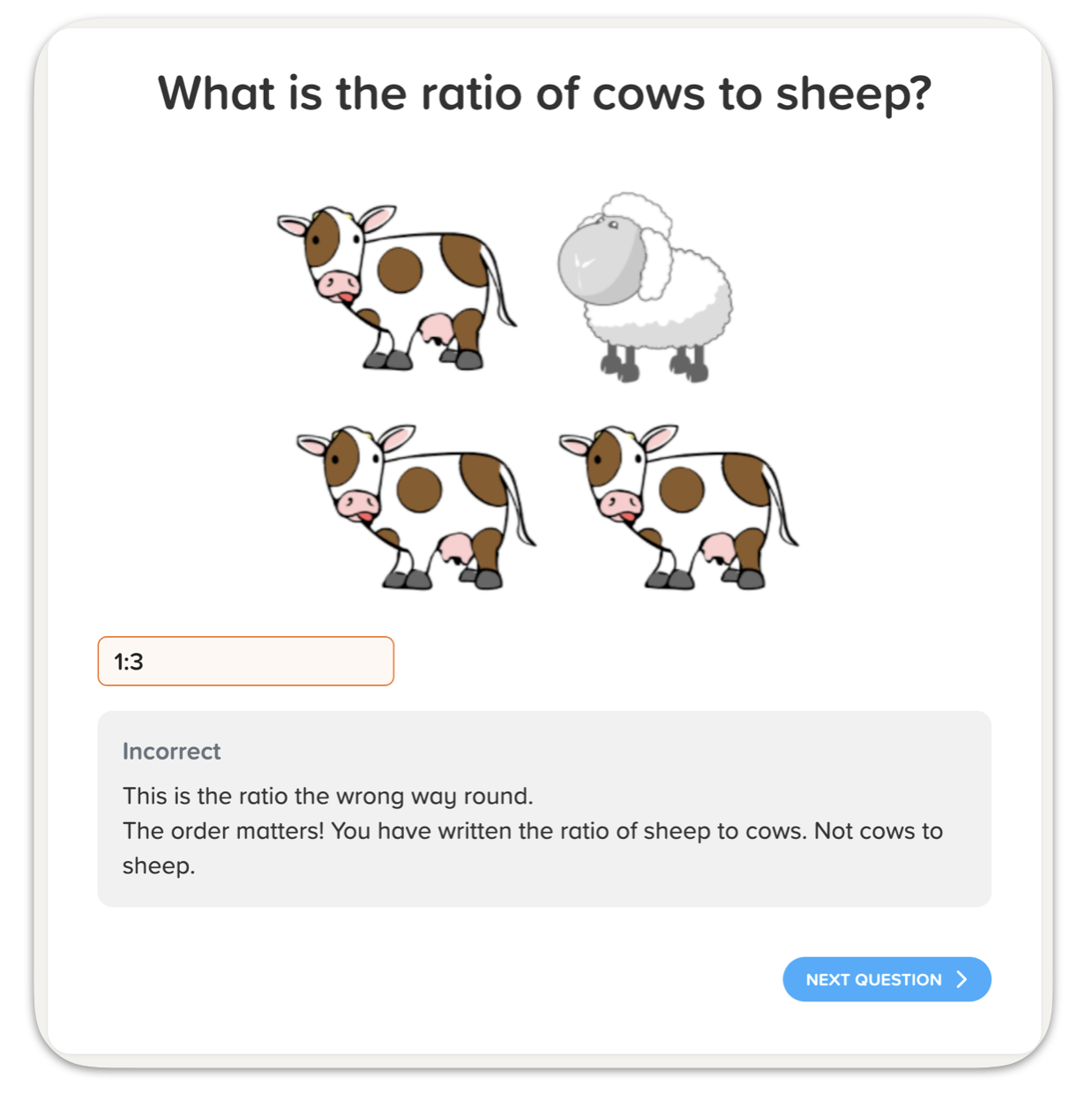

Feedback is also vital in improving metacognition. The above example may be simple, but it is a classic misconception. Here the student is receiving pertinent feedback – they are not going to be simply told the correct answer. We want a learning episode to occur. This type of feedback, coupled with various forms of learning material and the ability to try again, improves learner retention and gives them the agency to self correct.

I have highlighted a handful of examples of how CENTURY can support formative assessment. My examples are by no means exhaustive and, as always, we in the Curriculum team are always keen to discuss our work and demonstrate how CENTURY can support you and your students.

To find out more about how CENTURY can help your school, book a demo with our team.