Estimated reading time: 12 minutes

Assessment has been under the spotlight in the last year, with many educators now wondering how it will change after the pandemic.

Earlier this year, we held an online event with former teacher, education consultant and best-selling author Tom Sherrington to hear his insights on the purpose of assessment and how more effective assessment systems could be developed to complement and enhance the learning process. Here's what Tom had to say.

If there were no public exams and no accountability system, teachers would still assess students and they would still want to assess themselves. Why? Because assessment isn't really for other people, it’s for ourselves.

An effective assessment system should reinforce our idea of standards, because they are an inherent part of understanding how we are doing in the learning process and that understanding is something we all value. Standards are not a controversial thing – they only become so when they have high stakes and doors are closed to anyone who doesn't meet them.

So, if not to impose limitations, what purpose do assessments serve? They should provide feedback to students that will help them answer the questions that they should always be asking themselves, like ‘have I explained it well?’ and ‘how could I improve?’.

And they should be used to promote student agency – students need to have the capacity to direct themselves towards their learning goals. If assessment inhibits that, demotivates them, or doesn't provide them the guidance about where they need to go next, it's not useful for anyone. Whereas if it keeps them focused, motivates them, increases the level of challenge and gives them actionable feedback, it's really going to enable them to make progress.

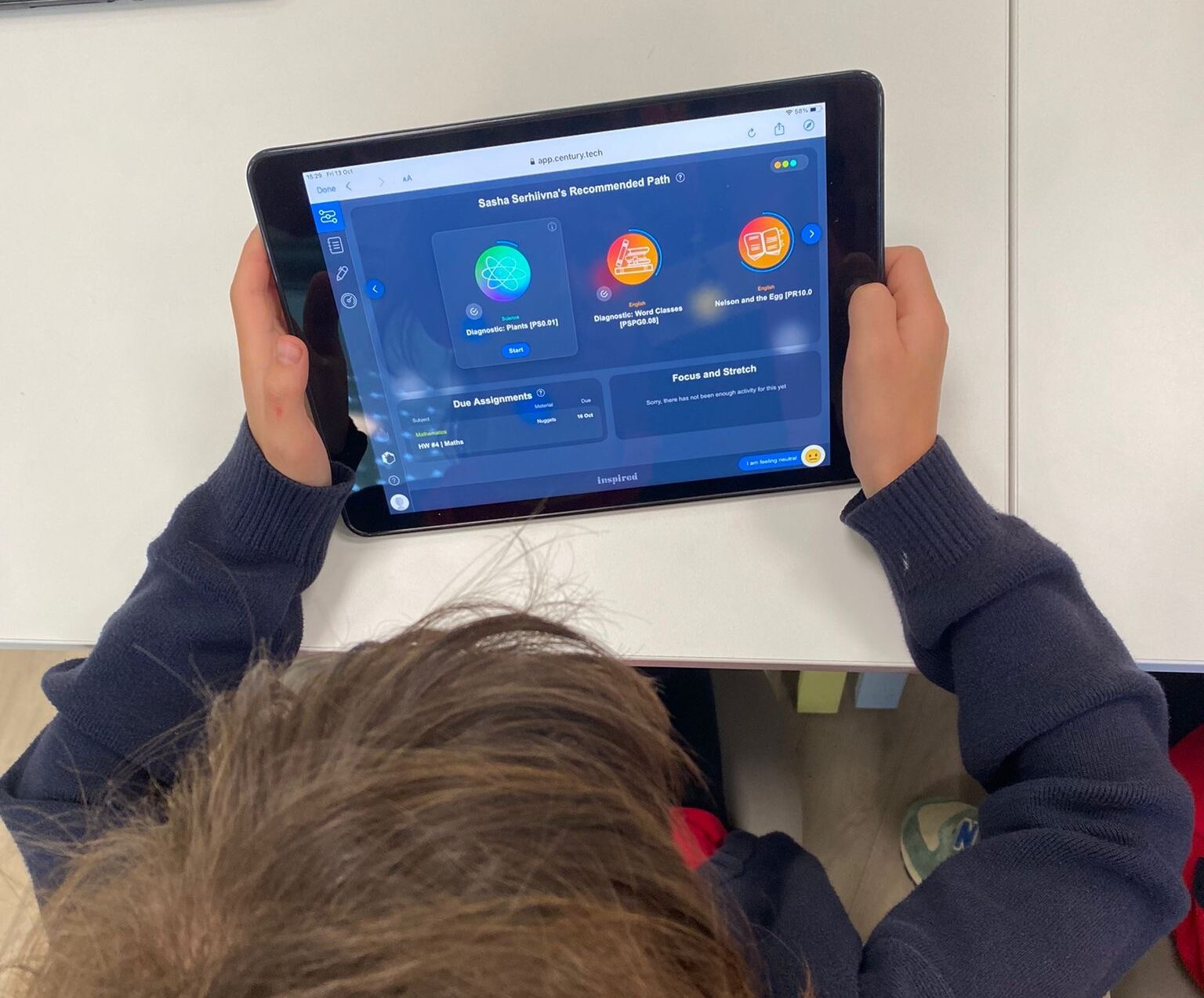

AI needs to enable those things if it’s going to be any good in education, and that's obviously what technology like CENTURY has been designed to try to do, because some of those things are easy to do when you're working with one student and hard to do when you're trying to teach 30 children all at once.

Using assessments to develop self-awareness

The main focus should not be reporting up, it should be feeding information back into the learning process. After all, does it really matter that you've got a whole pile of data on a system that's shared on a server if nothing is changing as a result of you having access to it? Data can certainly be useful, but it’s what you do with it that matters. If testing is going to have an effect on the learning process, it needs to have an outcome that will help students to develop a sense of themselves as learners and an awareness of what else there is left to learn.

For example, when I was playing the guitar the other day, I had a sense of the process that I was trying to undertake and there was a quality aspect to that, which was “does this sound good? In what sense am I improving, if I am?”. I have a kind of sense of myself as a guitarist that is informed by things like hearing what a lot of other people are able to play and how well they can do it.

Having an awareness of our limitations motivates us to try to address them with some intentionality. We can only actively select things that are more useful for us to do than others to help us improve if we have an awareness of our own capacity. That’s why the sense of self is such an important part of the learning process.

So ‘how am I doing?’ is a question we should be getting our students to ask themselves all the time, and there are different ways to ask it to inform their sense of progress, for example:

- "Can I explain it well enough?" – in other words, in terms of their discourse, can they explain it well enough given the context they’re in and for the purposes of what they’re meant to be doing? That isn’t the same as just ‘can I explain it?’. In my opinion, ‘can I’ questions aren’t satisfactory, because they’re too vague, and there's always another level of depth you could go into to contribute to discussions even more effectively.

- “Is my work good, and how would I know that?” – if they’re going to improve, they need to know what that would actually look like. If they don’t know where it is they want to be, then it’s difficult to move towards it.

We need to view this as an ongoing part of the learning journey. In order to reach ambitious goals, we have to take a set of small steps towards them. But each of those steps needs to have some meaning to us that can keep propelling us forward, and it is so important to stress that they typically don't mean anything if they’re expressed in terms of grades, percentages and scores alone.

It should look more like “okay, what words should I use instead when I'm writing?” or “I need to think about which maths operations I should be doing to be able to do this”. Ultimately, however we assess, it has to translate into something meaningful in the language of the subject at hand if the students are going to be able to act on that and improve.

This is why feedback is most effective as an action. For example, instead of “you did X well but you haven’t fully understood Y”, it could be asking them to redraft something or do more questions of a certain type to nail a difficult topic or getting them to re-explain something in a clearer way.

The need for instructional input

Imagine you see a group of teenagers in a skatepark – it looks like a perfect learning environment. It’s self-directed and requires creativity. It’s highly challenging, and that’s what makes it so motivating, because it's a great feeling when they pull a trick off. The rewards of doing well are huge, and even though there’s a high failure rate, they don’t mind because the rewards of success are so great. The skateboarders are constantly having to make choices about what to do next and learning through peer communication and by seeing, ‘wow, I didn't even know you could do that. Let me see if I can do that’. What’s more, the feedback is immediate – they don't have to wait a week to find out if they've succeeded in skateboarding, and they can tell for themselves because they were the ones who set their goals.

It’s intrinsically motivating and rewarding, and that's why people choose to spend hours down the skatepark. So, surely the lesson to learn from this is that we need to let children develop their creativity and problem-solving skills with less instructional input from us?

But here's the kicker. Most kids don't go skateboarding because they think it’s too hard for them. They haven't got the initial sense that they could ever do it at all. Likewise, to get most children to get to the level of confidence that will allow them to be self-directed learners, they will need a lot of guidance and instruction from teachers first.

We have to tread lightly with the zeal for creative independent innovative 21st century thinkers. Most children need to be taught secure knowledge in a very disciplined instructional way in order for them to get to the point where they can be creative with knowledge.

The difference between the learning zone and the performing zone

The idea of the ‘learning zone’ and the ‘performing zone’ are well-expressed in a TEDx talk by Eduardo Briceno with the angalogy of a Beyonce concert. It’s a slick show where nothing goes wrong, but that’s not what it’s like in rehearsal. There, they review the show, break it down into small steps and practice over and over and try different things out, and of course get some of them wrong, and it’s this learning zone that allows them to perform at such a high level when they need to.

The same applies to education. Students do need to be able to kick it up a notch and perform under more pressure when it comes to things like summative assessments, but in order to be able to do that, they need to learn in a space that feels safe and improvement-focused. Lessons shouldn’t feel like a performance zone all the time, and it shouldn’t feel awkward to be wrong.

That is also a skill that they’ll need in later life. For example, in my job I need to present to large numbers of people, and that’s my ‘performance zone’, but to be able to do that, I’ve had to do a lot of preparation and work behind the scenes.

Considerations when developing a system of assessment

We have to have a sense of a ladder of difficulty. Obviously, there’s an inherent conceptual challenge involved in answering questions that will vary depending on the content being assessed, but there are a lot of different factors that can be included, such as the idea of recency (a question on a topic covered months ago will be more challenging to answer than if it were taught that week) and prompting (‘could I spontaneously figure things out using prior knowledge without being prompted to do so?’). These all add to difficulty, and a good system of assessment will vary the parameters to challenge students within a knowledge set.

Designing assessments requires a lot of thinking so that we remove various levels of support and add complexity so that the same subject material is presented in different ways, allowing students to study it at varied levels of depth.

Knowing how to scaffold up levels of challenge so that students are always going deeper is such an important skill. To prepare learners for their future, we need to also be assessing them on their practical skills.

If you asked a group of students to make a motor work, then to make it go faster and then to turn in different directions, some of them may be able to do that. Then if you ask “okay, now can you use maths to measure the forces to make some calculations?”, it may be that a different set of students will be able to do so, but that knowledge isn’t inherently better than the knowledge required to make it work.

That’s not to say that learning knowledge is less important than it used to be. If we want physicists to be able to land helicopters on mars, we are certainly going to need them to know their stuff – a knowledge-rich curriculum is still very relevant to the needs of industry in the 21st century. But we also need people like engineers who can use their hands and make things, and we should appreciate that that’s an important skill set too. Both of them have value, and the way we assess learners should reflect that.

Book a demo to find out more about how CENTURY can help to enhance the teaching and learning at your school or college.